History of Window Glass

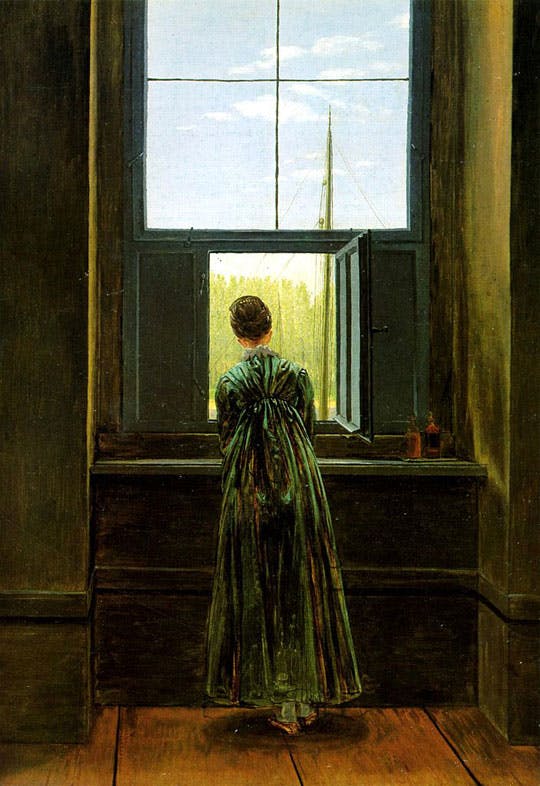

Caspar David Friedrich, Woman At A Window (1822)

In the past glass was a precious material, so highly valued that only the wealthiest homes had glass in their windows. And most homes had no glass. So how did we get here from there?

Glass making was an advanced process during the Roman era, and many ancient homes had glass-paned windows. The very early windows were panes of glassy pebbles set in a wooden frame. These windows would let some light through, but were not completely transparent. Clear glass panes were first invented in the late 3rd century CE, when glass makers began blowing a cylindrical bubble of glass and then slicing it lengthwise and then flatten out the results.

During the so-called Dark Ages, this technology, like so many other technologies and comforts known before the Fall of Rome, somehow got lost. While cathedrals across Europe made use of stained glass for their windows, domestic windows were totally unglazed, with only wooden shutters to keep out the cold. Some people took thin animal hides (or parchment) and soaked them in oil to make them as translucent as possible. They also had to keep their windows (and doors) pretty small, to minimize the drafts, and whenever possible, curtains or mats further helped with insulation. This is why interiors were so dark back then, with the never-extinguished fire providing most of the light.

Then, during the Middle Ages, glassmakers began once again to develop ways to make flat window glass. In the 14th century, French glassblowers developed the process known as crown glass, where a hollow bubble of glass was then centrifugally spun into a flattened disc. You’ve seen old-fashioned windows using this technique — it looks like bottle bases inside lead panes. Meanwhile, other glassmakers revived the ancient cylinder glass technique. These ‘new’ technologies made it possible for the very wealthy to afford glass in their windows. Cylinder glass only yielded small squares of glass, and the crown glass discs could be cut into diamond-shaped pieces, or diapers, with minimal waste, so that’s why you see a lot of diamond-shaped lattice windows from the Tudor era.

By the mid-16th century, window glass was increasingly common. But even for the wealthy, it was still a luxury: upper-class houses still only had glass in the windows of the most important rooms; by the end of the century, the nicest middle-class homes had glass in about half their windows. And for those aristocrats who spent months in each of their various estates, their window glass was such a precious commodity that they had it taken out and stored carefully in their absence.

Many 17th century engravings and drawings show lattice windows in various patterns. The lattice was made out of lead, so these are called leaded windows. You can also see a range of window types: casement windows were the most common, opening inward so as to protect the delicate glass. By the 1680s, it was not uncommon to see wooden-framed, square-paned sash windows in the grander homes, and it was around this time that the weighted sash was invented, which meant that when you opened the window, it would stay in place without sliding or being fastened.

Meanwhile, French glassmakers had figured out how to cast glass, yielding flatter and clearer panes than ever before. The perfect showcase for this new marvel was Versailles, built in the 1680s, and particularly the staggering Hall of Mirrors, with its facade of cast plate glass windows reflected in matching plate glass mirrors.

For the next century or so, different engineers in different countries vied to create the strongest, clearest, flattest window glass, using various recipes and techniques. By the middle of the 19th century, wealthy Brits were using the latest materials in their glass greenhouses or conservatories. And in fact it was a gardener who designed the most famous glass structure ever, the Crystal Palace, the site of the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London.

No one had ever seen so many windows before, and not just because of the glass technology — shortly before the exhibition, England had repealed two duties on windows and window glass that had drastically increased the cost (it had been introduced as a proxy for income tax, since the wealthier one was, the more windows one had). So the Crystal Palace was a stunning display of plate glass just in time for it to cost about 50% of what it had previously.

This was also the time that steel making was modernised by the Bessemer process, allowing steel to become the major component of architectural structures. No longer did walls have to bear the weight of the structure — now the steel frame supported the building, and the walls could be made entirely of glass, a feature known as a curtain wall.

The curtain wall found its apotheosis in skyscrapers like the Lever House, which featured the first curtain wall installed in New York City, in 1952. Of course, glass and glass making technology have only been improved upon for the last 150 years, and now we have strong, insulated glass in whatever size we want. But it’s interesting to think of how recently it was a luxury out of reach of the average person.

| 1216-1398 AD, the High Middle Ages, saw the introduction of Gothic and early English church architecture with much larger windows openings comprising smaller leaded panes. |

| 1399 – 1484 AD, the Late Middle Ages, introduced Perpendicular Gothic and the Baroque styles, both highly decorative and intricate styles. They are distinctive from earlier windows in the form of the arches at the top. Early gothic arches were ‘two centred’ tall arches whereas the later perpendicular form has a low ‘four centred’ arch. |

| 1485 – 1602 AD, the Tudor Period, saw the extension of substantial building from the ecclesiastical/royal/military areas towards domestic buildings, examples of which still exist. |

| 1603 – 1713, the Stuart Period, showed little architectural development and instead concentrated mainly on war. The Great Fire of London in 1666 necessitated large scale re-building and introduced the neo-Classical style, with for instance, Christopher Wren (St. Paul’s Cathedral). |

| In the Georgian Period from 1714 – 1836 AD. The neo Classical styles were continued. Larger clear panes in a timber lattice (astragals) were used. |

| Victorian windows, from 1837-1901 AD, used even bigger panes and fewer astragals. During both the Georgian and Victorian periods, dramatic increases in the numbers of domestic dwellings with windows occurred. |

| One of the predominant styles of the early 20th Century was Art Deco which frequently utilised metal-framed windows with minimalist designs and some highly experimental forms, including curved glass and nautical engineering styling |

If you want Professional Cleaners – Call us today 07940 575 999 or contact us for more details or to provide a free, no obligation window cleaning QUOTE. We cover window cleaning in Burnley, Blackburn, Accrington, Clitheroe, Whalley, Padiham, Great Harwood, Darwen and the surrounding areas of Lancashire. If you are not sure about your area, just give us a call.

Specscart buy glasses online uk are recommended by WFC Window Cleaning

By Bernadette Kyriacou

Tags: Domestic Window Cleaning, History of Windows